It is necessary to offer a simple and obvious basic formula for the horror film: normality is threatened by the monster…. The definition of normality in horror films is in general boringly constant: the heterosexual monogamous couple, the family, and the social institutions (police, church, armed forces) that support and defend them. The monster is, of course, much more protean, changing from period to period as society’s basic fears clothe themselves in fashionable or immediately accessible garments—rather as dreams use material from recent memory to express conflicts or desires that may go back to early childhood.

-Robin Wood, An Introduction to the American Horror Film, 1979

With Halloween right around the corner, I am once again fully engulfed in a season-long horror movie marathon, complete with slashers, final girls, supernatural haunts, and monsters dredged up from the depths of our own psyche. Having grown up in a very religious and conservative home, I did not always have access to—or literacy around—horror films, but my childhood obsession with Scooby-Doo, Sabrina the Teenage Witch, and that one episode of Boy Meets World did eventually evolve into a healthy appreciation for a broad spectrum of horror fare.

What I appreciate about horror is that, on the surface, it may seem to exist to peddle blood, guts, and fear, but those are merely the devices and vernacular of the genre, not the objective. What draws the viewer in more than the jump scares and gore—and perhaps in spite of them—is what these horror stories have to say about us as viewers, about our social and cultural values, about what’s terrorizing us in our own life and mind. Horror is not concerned with telling us what we should fear, is not intent on convincing us of a new monster or a new threat, rather it serves to help us understand and process what we already do fear and what we do value, through its use of metaphor and social awareness. It reveals the monster we already fear, a monster that changes, shifts, and evolves to suit our ever-changing world and collective anxieties, that challenges our social institutions.

The horror genre works across time by constantly adapting to what events occur in the real world, attempting to both intensify the fear factor of its films, as well as help viewers process the societal fears they faced in reality by presenting them on screen. Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1941) and Rosemary’s Baby (1968) are no exceptions to this, the former reflecting concerns of evilness of man as Hitler rose to power and the latter reflecting fears of the occult and satanic practices, each utilizing the iconographies of their respective horror genre cycle and practices of the eras of film they were made in to enhance these fears.

-Emily Um, “How The Horror Genre Reflects Societal Fears Throughout Time,” 2021

Approaching the horror genre with this in mind makes each work an opportunity for exploration into the historical and social context within which it was made, for reflection on our own fears and anxieties, and for evaluating the elements that the film has used to elicit those fears and anxieties. Whether it’s the oft-repeated home invasion scenario as a metaphor for our own xenophobia or the sexual innuendos in Ridley Scott’s Alien as symbolism for a fear of our own offspring, these themes present themselves in different ways and to varying symbolic effect across the genre.

In the spirit of the over-arching theme of my nudity-centric blog, the recurring horror movie device that has piqued my interest for the purposes of this particular piece is not the phallic shape of the Xenomorph’s head or the foreigner-as-intruder trope but nudity and its wide array of uses within the genre. The naked body is not a rare sight in horror—especially women’s bodies—but it seems to serve a wide range of functions depending on its use, to reinforce Judeo-Christian ideas of morality, modesty, and sexual propriety, to incite a sense of unease, danger, and fear within the viewer, and to express themes of power, womanhood, and their threat to masculinity.

For the Wages of Sin is Death

Sexual overtones in horror have been commonplace for some time, but especially since the release of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960) and its subsequent impact on the horror genre, shifting the genre away from one-dimensional monsters to more nuanced, psychological ones. In her piece, “Of Monsters and Men: The Impact of Psycho on Horror Cinema,” Josie DiCapua describes this impact: “The film created an entirely new genre: the slasher flick… It brought America away from the nuclear, prepackaged scary movies of the time and flipped them over their heads.” It is in these slasher flicks that would come into popularity in the following decades where the nudity-laden “death by sex” trope comes to the forefront and exposes us for our own sexual malaise.

In Psycho, Marion Crane pays in blood for the repressed sexuality of her killer, Norman Bates, her nudity in the fatal shower scene drawing her femininity into the viewer’s focus and standing in as a symbol for the femininity in Bates. His fear of—and his need to destroy—the feminine in himself was turned outward against Marion. Subsequent variations of this theme, however, would instead punish the young, nude, and sexually active woman—and often her lover—for her own sexuality and supposed moral failings, hinting at a discomfort over sexuality that ranges from a distrust of the sexuality we don’t see to a disgust for the sexuality we do see, a fear of both the repressed and the expressed. Nowhere is the updated slasher formula more tried and true than in franchises like Halloween, Friday the 13th and Nightmare on Elm Street, wherein a young couple typically has sex (or, through nudity, is implied to have had sex) and is promptly punished with a violent death at the hands of an unrelenting monster that their surviving friends must outrun and outsmart. This formula taps into our own longstanding fears, social anxieties, and cultural stigmas around women, sex, and sexuality, especially as they can be related to Judeo-Christian concepts of sin, temptation, and damnation.

The morality-based trope of nudity and sexuality as punishable offenses in horror relies on cursing the sinners and blessing the saints or, in horror movie terms, killing off the sexually impure and rewarding only the chaste with survival. This also aligns nicely with coming-of-age narratives—it’s no wonder it’s often young adults just coming into their bodies and their sexuality who suffer the wrath of the Michael Myerses, Jason Voorheeses, and Freddy Kruegers. In this reading, nudity equals sex, sex equals Biblical sin, and Biblical sin warrants damnation by a higher power—or a sexually repressed maniac. A more modern interpretation of this trope, however, may also see this as an invitation to live life more fully in spite of the ever-looming and inevitable threat of death and damnation:

In the absence of God, secular society has built the church of the horror film. They both have robust morality structures but what distinguishes modern horror cinema from say medieval Catholicism, is that rather than promising a shot at Heaven to lend meaning to a life that is ‘solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short’ (Leviathan, i. xiii. 9), horror films can use terror to invite us to live as fully as we can, knowing that it’s just a matter of time before death finds us.

-Sasha Wilson, “The Naked Bodies of Horror Lay Bare the Inevitability of Death,” 2021

Depending on one’s interpretation, the “monster” in the death-by-sex trope could either be sexuality itself, the destabilizing force in society that threatens order and family structure, or it could be the looming oppression and damnation that would seek to extinguish it. Either way, the punishment for sin–or perhaps for life itself—is death. This formula is so frequently utilized and so thoroughly exhausted by the horror film genre that it has been explicitly detailed and parodied in meta-horror films like Scream (1996), The Cabin in the Woods (2011), and The Final Girls (2015), each treating the trope with a wink, a nod, and a subversive twist—even centering the horror film viewer as the monster—but all of which dutifully following the rules of the trope in one way or another, admitting the inevitability of death as the price of living.

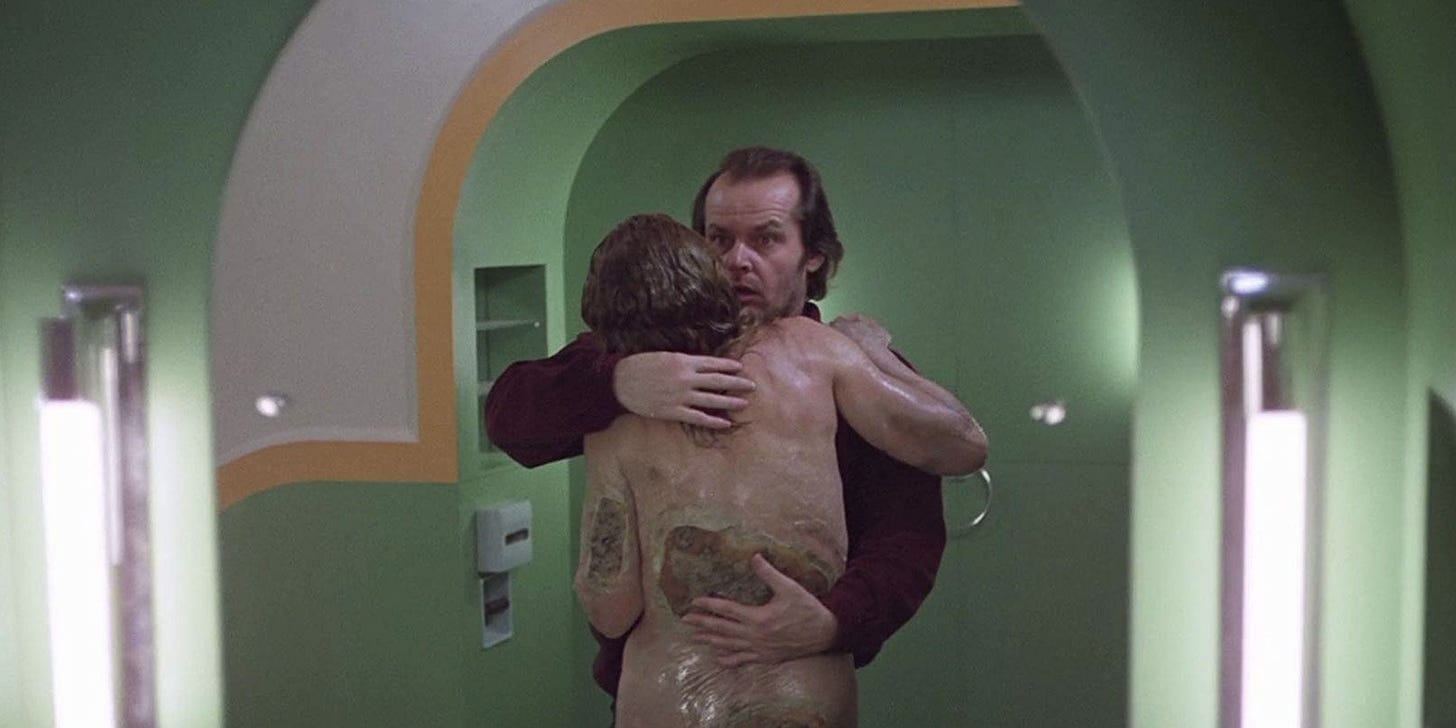

The death-by-sex theme also extends beyond the true slasher flick to other offshoots that incorporate nudity to similar effect. In Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (1980), nudity fulfills a familiar role—reminding the viewer of the their own mortality—appearing in the form of the ghost of Mrs. Massey, a former guest with a backstory of infidelity and sexual impropriety, sins for which she has already paid the price. The interaction between Jack and Mrs. Massey’s ghost may be brief, but serves to reveal the cracks in Jack’s psychological composure, betraying his own moral failings. She fulfills the role of temptation for Jack. Her initial appearance as a young and beautiful nude woman will also undoubtedly remind the viewer of the sensual, youthful nudity often seen in slasher films, but the scene quickly plays out her demise:

A famous example of employing nudity as a visual motif to underscore death’s inevitability is the woman in Room 237 of the Overlook Hotel in The Shining (Stanley Kubrick, 1980). She emerges from behind the shower curtain and her flesh rots from maiden to crone to corpse faster than your fingers prune in bathwater. Her cackle deliberately seems to remind the viewer “dust thou art and unto dust shalt thou return, (Genesis 3:19).”

-Sasha Wilson, “The Naked Bodies of Horror Lay Bare the Inevitability of Death,” 2021

We may see in Jack our own moral failings and inconsistencies as well, or a lack of restraint from our own temptations. The grotesque nudity in The Shining is not necessarily something to be feared in itself, but something that may incite a fear of our own eventual demise, our own deterioration, and the punishment we will all eventually face for living our lives. This fear of deterioration and decay in itself is not uncommon and can be seen in other films such as Ari Aster’s Hereditary (2018), among other recent films that have marked an uptick in this trend. In the final moments of Hereditary, the crowd of still, silent, nude bodies circling the family’s home seem to calmly and ominously portend the death of the Graham family. The bodies, of all sizes and many of whom aged, present not only a creeping, looming promise of our own death, but force us to confront another fear entirely, which may be even more haunting: Becoming old and undesirable, experiencing life after the beauty, youth, and attention have worn off and we become discarded ourselves.

“These characters are all monstrous versions of ‘respect your elders’,” argues Roxana Hadidi in Polygon, pointing out that a fear of old people’s treatment and their dissipated role in society haunts us all. She argues that old people are the ultimate fear in horror’s ‘Us vs Them’ stories because while one can avoid becoming a vampire, zombie or being murdered, becoming old is an inevitability. The “them” is even more frightening because that will one day be “us”.

-Tom George, “Old people are the new villains of horror movies,” March, 2022

The appearance of nudity in these cases, and in horror films in general, tells us nothing about any kind of morality or virtue or threat inherent to nudity, rather, it tells us about our own fears surrounding mortality, human fragility, aging, and death. It is a way to process and understand the anxieties and cultural stigmas widely held around nudity and our bodies, yes, but also our experiences of sexuality and vanity.

Something Wicked This Way Comes

Of course, not all horror uses nudity as a device, and not all nudity in horror is used to express or allude to sexuality, nor to the punishment thereof. In other cases, rather than punishing—or inspiring—a life fully lived, the effect may instead be to alert us to a rupture in the social order, where the impact serves to warn us that what we see before us is not exactly what it purports to be or to stir up a discomfort with our own primal nature, depending on our interpretations and fears.

Though it first uses nudity in a manner consistent with the slasher films we have already discussed, David Robert Mitchell’s It Follows (2014) deviates from the formula and introduces us to nudity that triggers our flight response, warning us of danger. In the film, Jay’s punishment for her sexual impropriety comes in the form of an unrelenting, slow-moving, socially oblivious stalking entity passed on to her by her sexual partner and which she is tasked with passing along to another sexual partner, lest the entity catch up with her—an obvious but impactful metaphor for sexually transmitted disease. The entity can assume the form of anyone known or unknown to her, but never quite exactly. When nudity appears in the film, such as in the case of the naked woman slowly trodding across the abandoned parking garage, the father standing nude on the roof of the house, or the mother carelessly loosing her breast from her robe, it is not the nudity itself that is a symbol of something sinister, rather it is the entity’s failure to adhere to social and contextual expectations, and perhaps also an allusion to impending death, as pointed out by Sasha Wilson: “The woman’s face is impassive and terrifying as it draws nearer and nearer to them. It is reminiscent of a body in a morgue, already on a slab. The nudity strips it of its personhood, its identity. It just becomes death, creeping toward you with steady inevitability on slow feet.”

There are other instances in horror, such as the impostors in The Faculty (1998) and perhaps also to some extent the varyingly clad walkers in Night of the Living Dead (1968), where the nudity is one of many signals to the viewer that what we are seeing poses a threat, the nudity and sexuality adding to the sense that something is off. While not strictly adhering to the definition, this failure to comply with social norms and behaviors carries some similarities to the uncanny valley phenomenon, typically applied to our averse reaction to increasingly life-like robotic and animated humanoids: The closer these non-human entities get to appearing human, while still failing to appear fully and convincingly so, the more unease we feel and the more our alarms are triggered of potential threat. A failure to appropriately comply with culturally established behavioral expectations, while otherwise appearing very close to normal, may not fall under this same phenomenon but the underlying, primal fear induces a similar aversion, especially within the heightened stress experience of a horror film.

Whether this is because their skin looks lifeless, their features are morphed or another slightly off factor, it could trigger an evolutionary feeling of aversion or disgust. The rationale being that there is a survival advantage in these feelings to avoid infection or contamination from a diseased human or animal.

-Alex Hughes, “Uncanny Valley: What is it and why do we experience it?” April, 2022

To piteous effect, the naked, monstrous “Mother” character in Zach Cregger’s Barbarian (2022) fails on every level to approximate normal human appearance and behavior, instead embodying tragic monstrosity, feral humanity, and raw empathy. In this film, our protagonists desperately seek to escape an underground compound where they find themselves face to face with a monster in the form of a towering, disfigured, nude woman. Her nudity, her scars, her pallor, her unintelligible muttering, and her complete disconnect from social norms strike fear in a way we've seen used in other films, but what is unique about Barbarian is that we as viewers are not only asked to fear this monster, but to pity her, as she, too, is a victim, a child born and held in captivity in the same chamber, motivated by her desire to mother and nurture a child of her own. While her nudity serves to expose her monstrous appearance and accentuate her feral nature, there's just as much fear in the realization that she, too, is tragically human, a monster created by the sins of humans more morally monstrous than she. Ultimately, the film points our ire at the true monster: the aging rapist and serial killer who fathered and held “Mother” in the compound, not unlike Frankenstein and his monster.

The Mother echoes Frankenstein, being a misshapen creature brought into the world through an unnatural process, unloved, isolated, and ultimately, sympathetic. She is the product of Frank’s monstrous crimes, and unwittingly carries on his legacy, through her desperation to nurture.

-Dani Di Placido, “The Monster In ‘Barbarian’ Is Unsettlingly Sympathetic,” October, 2022

Timely for our present-day moral panic, yet no less tragic and revealing of our own malaise is Sleepaway Camp (1983), which promises a classic slasher flick but then, again, uses nudity in a peculiar, unexpected way compared to these other films. Notably, it offers nudity as a final jump scare, not merely because the nude body is expected to incite fear but because we as viewers are expected to feel a particular fear and upset about this particular body and what it reveals about our hero-monster. Over the course of the film, our main focus is on young Angela, whose peers repeatedly goad her to disrobe for various reasons. She rebuffs these attempts to the increasing suspicion of the viewer until, of course, the reveal of Angela standing nude over what we now know to be her final kill of many, exposing her penis and masculine features to the viewer. While this novel twist was sure to surprise the viewer in 1983, it has also drawn modern criticism for rooting its monster in transmisogyny and fear of queerness.

By making Angela a whipping post for constant teasing she becomes the central character. In horror movie tropes she is set up to be the “final girl,” someone you rally around when she is eventually confronted with the incarnation of evil. However, Hiltzik subverts this idea by making Angela not the victim but the killer, and—in what the movie suggests is a worse transgression—not a girl but a boy. Sure, this surprise plot point separates Sleepaway Camp from countless other slasher films of its day, but more importantly, it is also its undoing. By venturing into the complicated gendered territory first explored by Hitchcock’s fascinations with violent queerness in Murder! (1930), and in Psycho (1960), the film portrays the transgender female body as monstrous and murderous.

-Willow Maclay, “‘How Can It Be? She’s a boy.’ Transmisogyny in Sleepaway Camp,” Cléo, vol. 3, issue 2: Camp, Summer 2015

The terror of that final scene relies on an anticipated discomfort with queerness, with queer bodies, and with the breaking of gender expectations. Through the big reveal, we come to understand that Angela was assigned male at birth and that she has long feared the discovery of that fact by her peers. What we don’t really know is whether Angela truly identifies as female, though it is implied that the decision to live her life as a girl was not hers, which is a fear-inducing scenario on its own and could warrant a critical reading that sympathizes with Angela as the true victim and her Aunt Martha as the true monster, having forced Angela to live as a gender other than her own. In either case, the shock nudity in the film betrays the viewer’s intrinsic fear of hidden queerness, repressed gender and sexuality, and the denial of one’s true self. Curiously, as Willow Maclay alludes in the above quote, these themes and revelations are not entirely dissimilar to those found in 1960’s Psycho, but the interpretation of that similarity is subjective.

Of Witches and Women

In a defiant move that upends our expectations of nudity in horror, the heroine of Happy Death Day (2017), Tree Gelbman, fed up with reliving her own murder Groundhog Day-style, takes advantage of her plight by strolling through campus nude, free of consequences or retribution. In a delightful departure from appearances of nudity in other horror films, Happy Death Day revels joyfully in breaking social expectations around nudity as long as the rules of life, death, and time have also gone out the window. We are not meant to feel fear at the sight of Tree's nudity, nor to understand it as a portent of her demise, but to laugh alongside her as she gives in to the absurdity of her predicament and signals that she has overcome her own fears and has committed to resolving them. All of this is to say that her nudity marks her command of her destiny; it signals her strength rather than her weakness.

While nudity as a reference to power and strength is fairly common within the horror genre—particularly among women characters—it is rarely used with this sort of joy and silliness. A much more common function of female nudity in horror is, yes, to embody power and strength, but also, in so doing, to jostle the male viewer and his fear of powerful and strong women. Witches, of course, are the obvious extreme of female power and, therefore, the obvious horror device to unsettle the male viewer, even when the witches in question are more hero than monster.

In Brian de Palma’s film adaptation of Stephen King’s popular novel of the same name, Carrie (1976), we witness just such a fear tied to the titular Carrie White’s blossoming telekinetic power. In its initial scene, nudity plays the important role of exposing our hero-monster to us for the first time just as she experiences her first period, nude in her high school locker room showers. She mistakes her own menstruation for a medical emergency, grasps at her classmates for help, and is instead ostracized and tortured by a gang of partially clothed classmates, inflicting shame and throwing tampons at her. From this initial scene through to the blood-soaked finale, the themes of womanhood, repressed sexuality, and the surrounding religious stigma are clear, represented by Carrie's telekinetic powers, her mother's abusive behavior, and her classmates’ torment of her. In the case of Carrie, the nudity itself does not serve to strike fear but forces us as the viewer to experience her fear with her and also to grasp the parallel of her burgeoning womanhood with the onset of her telekinetic powers.

The ‘dangerous’ link between the witch’s power and menstrual blood is omnipresent in Carrie. In the first scene, viewers witness the onset of Carrie’s first menstruation. This moment can be seen as one of horrific monstrosity as Carrie ogles the blood in fear and disgust. However, it is also the catalyst for Carrie’s empowerment as a young woman. The menstrual blood signifies Carrie’s entrance into adulthood – she is no longer an undetermined figure balancing on the threshold between girl and woman. It is no coincidence that, in the film, Carrie’s menstruation seems to run alongside the onset of her telekinetic powers.

-Lakkaya Palmer, “Carrie White as Witchcraft, Power and Fear,” June, 2021

The connection between womanhood and witchcraft, of a woman growing into her physically and sexually mature body paralleled with supernatural power and control, is key to the fear that witches provoke in horror films. The use of nudity in these contexts focuses our attention on the woman herself, on her mature body, her sexuality, and, particularly, connects the woman with the primal, natural world over which she is supposed to have a supernatural command—or, at least, over which her male counterpart fears she might have command.

Witches have long been associated with nature and our “primal” side. They use their knowledge of herbs and plants for cures and potions. It is said that some witches have power over the elements and even the universe. They understand nature extremely well and whether it’s through white or dark magic, their rituals and concoctions entail natural ingredients.

-Beth Alice, “Femininity and Fear in ‘The Witch’,” May, 2016

Following this theme, what we witness in Robert Eggers’ The Witch (2015) is a microcosm of historically familiar events like the Salem witch trials, a hysteria that led to the execution of many of the women accused of witchcraft. In the film as in actual history, the idea of the empowered, independent, and sexually mature woman is just as monstrous as the actual witch. Like Carrie, The Witch’s Thomasin is also coming of age, her body is developing beneath her plain, period-appropriate garments, and the fact that this still catches the attention of her younger brother is enough to bring scorn to Thomasin. The looming Witch of the Wood and Black Phillip’s memorable “Wouldst thou like to live deliciously?” line frame the demise of Thomasin’s family, leaving only her alone in the end. Unlike Carrie, however, the appearance of nudity comes in these final moments rather than at the beginning of the film. Thomasin only embraces her femininity, womanhood, and power once she is freed of her family and escapes to the woods to join the other witches in their nocturnal gathering, dancing naked around the fire and ascending into the sky, finally free of the shackles of men and puritanism. Nudity here embodies freedom, power, triumph, and a feral connection to nature, which may well stir fear in a viewer comfortable with the subjugation of women and the natural world.

On the subject of witches, it's no wonder that Anna Biller’s The Love Witch (2016), the only film on this list directed by a woman, is the film that leans most heavily into using nudity as a signifier of power, strength, desire, manipulation, and control, rather than for shock value. By no means, however, does this mean that there is less fear elicited in the film, but that that fear is a spellbinding one couched in technicolor stained glass, crushed red velvet, and psychedelic visual effects. In adherence to our cultural understanding of witches in popular culture, our hero-monster Elaine commands and connects with the natural world by way of herbal and chemical potions (which, notably, resemble a child’s backyard “soup” concoction), controls men, their desires, and their love with her sensual gaze, and, most terrifying of all, cannot seem to control the strength of her own magical abilities, nor does she seem to care to try. If fear of powerful women is what drives the witch trope in horror film, Elaine’s vapid disregard for the trail of dead male suitors in her wake is undoubtedly a bubblegum nightmare for the male viewer. For women viewers, there may be something more meaningful in Elaine’s comfort with her body, her nudity, and her sexuality: That it’s ultimately all in service of herself and not a man.

It's about male projection onto women that they're a witch, either an evil witch or a sexy witch. And then the difference between that is a woman's interior experience of herself and her own power, which can sometimes include or encompass sexuality and beauty and glamor, but not necessarily for the sake of men.

I think one reason young women respond to [the movie] is because this is what they're going through. They want to use their own feminine beauty and power and glamor as their own power, but not necessarily in the service of any man, in an actual witchy powerful way…

-Anna Biller, as interviewed by Sadie Bell for Thrillist’s “Pulp Novels and Hitchcock: All of Anna Biller's Inspiration Behind 'The Love Witch',” October, 2021

The fear of the fatally independent, clumsily powerful, confidently nude, and irresistibly sensual woman—the eponymous love witch—is the monster at the heart of The Love Witch, but there are other instances of nudity in the film that garnish that fear, notably the male nudity. This arrives most prominently during the wedding ceremony, where we see nude men and women alike, participating in ritual and celebration. These moments are not dripping with fear, and you might say they appear joyful and natural, but in the context of feminine power and desire found in the rest of the film, the discomfort one might expect to come from these nude men is their juxtaposition to—and equal standing with—the nude women around them. That these men are nude also does not serve the straight male gaze which is so prominently centered in other horror films like the slashers flicks we’ve already covered, further reinforcing the idea that no part of this film is in service of men. The men in The Love Witch are either casually used and discarded or are denuded of their power and status, which certainly taps into the same masculine anxieties at the heart of the witch trope.

Mirror, Mirror

Whether it’s nudity, witches, sex, or slashers, it is through these tropes and devices that horror offers an opportunity for reflection upon our deepest fears and discomforts, upon what we feel threatens the stability of our world and our social institutions, be they what they may. The naked body occupies an important space in horror precisely because it is already cause for much turmoil, discomfort, and vulnerability in our everyday lives and in our deepest psyche, regardless of how we may personally feel about our own body or the bodies of others. We understand that there is a personal, cultural, and societal fear associated with nakedness and femininity, and we bring that understanding with us to the theater, the silver screen… the great mirror that it is.

The next time you turn on a scary flick, whether it’s this spooky season or some time in the distant future because you’re not really a fan, I hope you’ll keep this in mind: The monster on the screen is something inside ourselves. It may not be a naked woman hobbling towards us in an abandoned parking garage or a naturist witch with red lipstick and a body count, but there’s always something on the screen to learn about who we are, what we value, and what we fear, and it may not be what it seems on the surface.

Sleepaway Camp is additionally problematic because even inasmuch as it goads the viewer into sympathizing with the transgender character's plight, it does so in a way that feeds into a stereotype whose prevalence is frequently exaggerated by transphobes, representing the fear of forced transitioning.

This is just one of many examples of really poor treatment of transgender characters in films of this era (and probably up to today), who are irrationally and disproportionately depicted as homicidal maniacs. Which is really no more than a reflection of a really poor understanding (and subsequent fear) of the transgender experience by the public at large.