“Forget them, Wendy. Forget them all. Come with me where you'll never, never have to worry about grown up things again.”

― JM Barrie, Peter and Wendy, 1904

Surely many of us have some childhood memory of Peter Pan, the boy who never grew up, who fearlessly taunts and spars with the dreadful Captain Hook, who resides in Neverland and epitomizes youthfulness, childhood wonder, and a life free of care and responsibility. My childhood knowledge of Peter Pan was limited to just a couple of viewings of Walt Disney’s 1953 animated adaptation and its cultural reverberations—Tinker Bell, for example, has long been a household name whether or not you’ve read the book or seen any film or stage adaptation of it. In my young mind, it was a story of kids like me clinging to childhood, magicked away to an imaginary land where they could avoid growing up and the looming responsibilities and doldrums of adulthood. What a dream: Eternal childhood! The story largely slipped from my consciousness as I grew older which, funnily enough, is also what happens to the adults in Peter Pan. I recently turned the film on, though, for some work-related research (and for a little personal enjoyment) and realized that the story I remembered from childhood was not at all the same one playing out before my now-adult eyes. I’ve been ruminating on it ever since.

Peter Pan, it turns out, is not so much the story of a heroic, magical boy who rescues children from their fate of growing up, but of a girl at the nervous edge of adulthood coming to accept that it’s time for her to say her sweet goodbyes to childhood. It was always about growing up, by exploring and saluting the wonder of childhood imaginations, sure, but also by recognizing when it’s time to bravely move forward. It’s obvious to me now but apparently child me was not interested in hearing that message just yet.

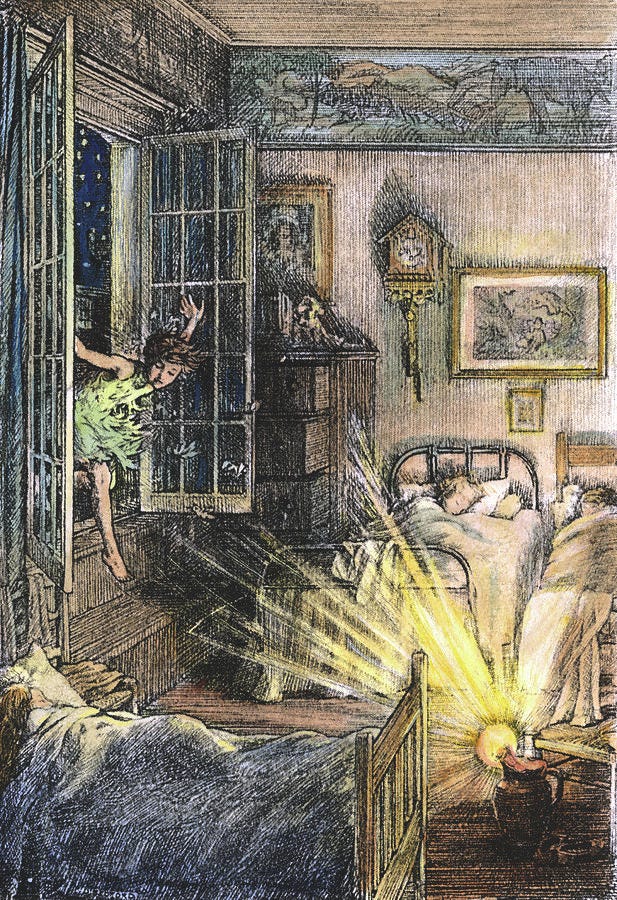

English author JM Barrie first wrote of Peter Pan in his 1902 novel Little White Bird and again in 1904 in the eponymous play Peter and Wendy, which is the story most of us know in some form or another. In it, Barrie spins a tale of three children, Wendy and her two younger brothers, who are swept away by Peter Pan to explore, adventure, and shirk responsibility in the woods and mermaid lagoons of Neverland, a place where little boys and girls never grow up. It is no coincidence that during the late 19th century and early 20th century, a subtle, renewed interest in the minor Greek god of glens and valleys, Pan, was rumbling in the literary world, stirring thoughts of pastoral simplicities and a time before modern, industrialized life. Barrie alludes to the connection between Peter Pan and the god Pan in Little White Bird, in which he presents Peter playing the flute to fairies and riding a goat (classic Pan behavior). With this historical context, Peter Pan’s embodiment of pre-adulthood and pre-industrialization makes sense, invoking a rebuke of modernity, order, and personal responsibility, opting instead for dreams of faraway lands, fairytale creatures, and childish ideation. He represents that anxious space between asleep and awake, between carelessness and accountability, between childhood and adulthood, and though he himself clings to childhood, the story offers an important lesson in growing up and, by extension, in adulthood.

By the way, I promise it’s purely by accident that I am once again writing about the Greek god Pan.

Barrie may have written about clinging to youth, accepting when it’s time to grow up, and holding reverence for those childhood memories 120 years ago, but those themes are just as relevant today and can be found in some of our current anxieties around adulthood, childhood, and nostalgia. At the extreme negative end of the spectrum, the outright refusal to rise to the responsibilities of adulthood has come to be known as Peter Pan syndrome, for example. At the other end of the spectrum, however, is the rise of “kidulting,” a trend of embracing childhood toys, media, and pastimes, primarily among Millennials and Generation X. It may come as a surprise, but this trend is believed to actually have positive emotional and social impacts, sparking joy and fostering connectedness for those who share in it. Whether we’re talking about Disney adults, adult fans of LEGO, 2023’s Barbiecore boom, rewatching Friends for the hundredth time, or, say, running around naked in the woods, it’s clear that today’s adults are reveling in the memory of simpler times, before adulthood set in with all its obligations, disappointments, loneliness, and struggles. That’s not a bad thing, and it’s clear it’s not a trend unique to our times, but one that scientists have confirmed is essential to our mental health. It turns out that applying the salve of nostalgia to our grown-up wounds is a natural response. It’s a reminder of a life well-lived, of the meaning of life itself, and of the people and experiences we hold dear.

“Nostalgia compensates for uncomfortable states, for example, people with feelings of meaninglessness or a discontinuity between past and present. What we find in these cases is that nostalgia spontaneously rushes in and counteracts those things. It elevates meaningfulness, connectedness and continuity in the past. It is like a vitamin and an antidote to those states. It serves to promote emotional equilibrium, homeostasis.”

— Dr Tim Wildschut as quoted by Tim Adams, “Look back in joy: the power of nostalgia” for The Guardian, November 9, 2014

In my years running around naked (by which I mean in all my involvement with the nudist community), I have long sensed an underlying culture of this same kind of reverence for something lost, something simpler, something free of the hierarchies and strictures of modern life. It certainly seems that those same pastoral dreams and escapist aspirations behind Peter Pan can also be found in the history of the nudist and naturist movements. It was, after all, during the same decade as the publication of Barrie’s Peter and Wendy, smack dab in the middle of the aforementioned Pan revival, that a series of publications by German thinkers Richard Ungewitter, Heinrich Pudor, and Adolf Koch presented and explored the concept of freikörperkultur, or free body culture, a philosophy of communal nudity, health and sport practices, leisure, and an embrace of the natural world. By all accounts, German ideas of freikörperkultur offer many of the same nostalgic reveries as the Pan renaissance, longing for a return to nature and a more idyllic life. As these ideas spread and reached the United Kingdom, the United States, and Canada in the 1920’s and 1930’s, some of the original ideas core to freikörperkultur were lost or adapted for their respective nudist communities, but the pastoral dreams, the embrace of leisure and simplicity, and the escapism from the modern, civilized world remained. Twentieth century British and American nudists fled their urban environments for the wild countryside, for remote campgrounds and lodges, for streams, forests, and verdant glens where they could disrobe, shed their worries, and revert to a slightly less civilized, les modern, less industrial state.

Today’s nudist and naturist communities still cling to that escapism, that perpetual pursuit of simpler times, a simpler life, a more joyful existence, a shunning of life’s trappings and signs of adult responsibilities (you know, clothes, etc.). Nowadays that tends to look more like vacation resorts, RV parks, beaches, and campgrounds than the aforementioned untamed wilderness, rugged lodges, and otherwise scrappy gatherings. That escapist pursuit, though, is kind of the point. The nudist community and nudist spaces tend to feel almost Neverland-ish, often unrealistic and idealistic on their own, free from our daily duties and worries and stressors but full of the silly joy of grown adults running around naked. Part of its appeal is that it doesn’t make grown-up sense in the context of our everyday adult lives, often spent sitting in front of computer screens, wearing suits and ties, toiling away in concrete buildings, or stuck in traffic. Speaking from my own experience in the nudist and naturist community, I can attest that the nudist idea and its adherents can teeter between dreams of a better world and detachment from the real world and, much like a visit to Neverland, this can cause one to lose touch with the real world world and its responsibilities. “We should never have to wear clothes!” some particularly ardent nudists might shout. This cry is part of Peter Pan’s cautionary tale: We need to face the reality of adulthood and the modern world, too.

“I suppose it's like the ticking crocodile, isn't it? Time is chasing after all of us.”

― JM Barrie, Peter and Wendy, 1904

Alongside the escapism of the nudist idea, though, there is something else… something more mature than one might initially expect. Much like in the story of Peter Pan, that something is an accompanying, inevitable awareness of the ravages of time, pointing to a need to accept our humanity, our fragility, and our eventual demise. The emphasis on eternal youth must be balanced by the implied inevitability of adulthood, after all. The nudists’ version of Tick-Tock the Crocodile—Captain Hook’s stalking, lurking reminder of the real-world eventuality of aging, time, and death—is, however, a far gentler, warmer acceptance of time, aging, and hardship and can be seen through their effects on the body. Amongst nudists—nowadays a largely aged population—there is an open appreciation for the body in all its forms, and for the many shapes and appearances that the body takes over the course of a life. Wrinkles, scars, and sagging flesh are embraced if not cherished, and the mingling of the generations is touted as a means of educating on the stages of life. Yes, nudists have a penchant for the recreational abstinence from the trappings of modern life, but that resistance to today’s grown-up problems also offers an important opportunity for growth and acceptance. It offers a space to better understand our own bodies and our own life cycle, for one, but it also offers a space where we can better understand and appreciate one another. When social stigmas are broken down, when we look beyond the labels and classes that the world has applied, we might understand and relate with each other better both inside and outside of nudist spaces, and we might apply those lessons to our everyday life. That, I believe, is a sign of maturity, complexity, and intellect absent from the character of Peter Pan’s childish worldview, but very much part of Wendy’s journey through Neverland and very much part of why nostalgia is such an important emotion.

In Peter and Wendy, the exploration of and reverence for childhood adventure and wonder and joy is what drives the growth toward responsibility and maturity. It is the journey through Neverland that prepares Wendy for growing up. Similarly for the people who run around naked, if the enjoyment of nakedness, the stripping of social barriers and hierarchies, and the silliness of the whole affair should serve any purpose, it must be to help us grow, mature, and be at peace with the reality of life.

The story of Peter Pan has much to say about growing up, about childhood, and about saying goodbye to those carefree days but, taken on its own, it does not necessarily point to the same grown-up return to Neverland, the embrace of childhood memories, or nostalgia for simpler times. When considered in its historical context, however, and we recognize that the story stems from a literary movement in which adults, too, were dreaming of a return to such places and times, it is wholly appropriate to read a tale of nostalgic longing into Peter and Wendy. Our collective interest in returning to the story of Peter Pan through countless remakes and re-imaginings also speaks to the same. We keep coming back, generation after generation, decade after decade, because the message is still relevant and nostalgia is still restorative. If you would like a more succinct story of the importance of grown-ups returning to childhood memories and pastoral dreams to re-learn a valuable lesson that can be carried with them in the real world, 1991’s Hook, a live-action follow-up to Peter Pan’s original story, offers a clear perspective.

In Hook, Peter Pan (played by Robin Williams)—now going by the decidedly more grown-up, businessy name Peter Banning—has long left Neverland behind and has started a family in the real world with the granddaughter of his old friend Wendy Darling (played by Dame Maggie Smith). Peter, however, has lost all recollection of Neverland, of childhood whimsy, of imagination and joy. He has committed himself to his career at the expense of time spent with his family and, specifically, with his children, allowing his adult anxieties and stressors to negatively impact his interactions and relationship with them. Following a kidnapping by Captain Hook, Peter must venture to Neverland to retrieve, yes, his children, but also the memory of his childhood, something he desperately needed in order to become a better adjusted person in adulthood. Through his exploration of his old stomping grounds, he remembers how to imagine, how to play, how to make believe, and he learns how to better understand and relate to his own children. In doing so, he is able to save his children from Hook’s grasp, but he also takes that lesson back to the real world with him, where he is reminded to not give so much of himself to his work and to spend more time with his family, enjoying life. It’s the remembering and the dreaming that saves Peter Banning and brings joy back to his adulthood, putting his life and values into perspective. Life is its own adventure, it turns out, and it doesn’t have to be miserable and monotonous if we take care to look for the joy and wonder in it.

Wendy Darling: So... your adventures are over.

Peter Banning: Oh, no. To live... to live would be an awfully big adventure.— Hook, 1991

Ultimately, the point of all this Neverlanding, nostalgia-hopping, and elysian dreaming is that we cannot stay there, because there is not a real place, not a kind place, not a place where growth and maturity can stick, as much as we might want to. Instead, we must use those feelings and memories for good, we must carry our learnings back with us to the real world to make life better for ourselves and others. For the nudists and naturists I know, this seems to be the case or, at the very least, the goal: To shed everything, to feel free again, to rediscover ourselves and the simple joys of life and then, if all goes as planned, to feel that connection to nature and to others in our everyday lives, to appreciate the little things in life like a wrinkle or a scar or remember the feel of grass or sand under our feet while sitting in traffic or behind a computer screen. You can’t blame people for seeking out and cherishing those wonders of life or the memory of simpler times and, I think, we desperately need them wherever we can find them. As much as we may criticize or judge one another for our escapist hobbies, interests, and guilty pleasures, they contribute to our well-being.

Maybe running around naked in this harsh and brutal world is childish, impractical, escapist. It is not so different from escaping to Disneyland or retreating into a beloved film from childhood or participating in a Renaissance Faire. Maybe they’re all silly, but they serve a purpose. We run to these places, these physical places and these places in our mind, to remember and to explore. In our fugues, there is something to learn about what is lacking in our daily life. Maybe it’s the sense of wonder, maybe it’s joy and laughter, maybe it’s a connection with others or with nature. People have always needed these things. We certainly need to be reminded of them now just as much as audiences and readers in the early twentieth century needed the story of Peter Pan to remind them then. But it is just as important for all of us to remember that Peter Pan is not the hero of the story. Peter’s story is a cautionary one of the dangers of not growing up. For childhood is full of wonder but it can also be uncaring, irresponsible, and immature, in the same way that the natural world behind our pastoral dreams is, in reality, unforgiving, cold, and unkind. We need a little escape into our own versions of Neverland but we must be careful not to linger there too long.

The most unfeeling child of all, needless to say, is Peter Pan himself. He flits through the play and the novels, and he has flitted through a century of stage productions and movies, and one result of those flittings is that we regard him as airy and innocuous. In truth, he is mean and green, a mini-monster of capering egotism; could there be any more dazzling proof of self-regard than a boy who first shows up in pursuit of his own shadow?

— Anthony Lane, “Why J. M. Barrie Created Peter Pan" for The New Yorker, November 14, 2004

We all still need do a little Peter Panning—or perhaps a little Wendying. We can dream of green glens, we can dream of our favorite memories and better realities and simpler times, and we very well should. But there is a real world awaiting our return, full of tedium and expectations, yes, but also ripe for us to bring joy and adventure and growth into it. Despite his carelessness, Peter was certainly onto something when he first guided Wendy and the boys to Neverland: “Now, think of the happiest things. It's the same as having wings!” It turns out that’s kind of how it works in real life, too.

Why are so many of us so old? Some of us are waking up to what we missed during an accomplished career. We have more flexibility in how we spend our days. We have less to lose if friends and employers find out that we are running around naked.

Regarding the partial quote, “Wrinkles, scars, and sagging flesh are embraced if not cherished”, I would love to agree, and would especially love to truly feel this way myself. But not only have I not adopted this stance, but in 30+ years visiting various nudist clubs, I’ve never once encountered anyone who has espoused it. The idea attempts the impossible task of merging childlike idealism and mature pragmatism. Yes, nudist clubs, for instance, do help us to recharge and face the other, so-called “real world” outside the gates. And yes, within the gates we commonly see aged others and they see our aged bodies and we nevertheless try to have as much fun as possible via the various available activities and amenities. But no one fails to notice the limitations of our physical bodies; in fact, those limitations are often accentuated in nudist environments when we can no longer safely play volleyball on shifting sand; or when we donate our beloved racket to the club because we can no longer run; or when we simply watch younger people, who move so fluidly and effortlessly. The fact that few or nobody complains too much shouldn’t be mistaken for anything beyond mere acceptance (if that), and certainly should not be characterized as a cherished state. Age has happened to us, along with scars and other infirmities. We socialize and play naked as long as we’re able in spite of, not because of, these constraints. Nudism reminds us and others that our spirit, our ideal, ageless self, is still here, still observing, still engaging in some fashion even though our bodies can no longer keep up. If we are to adopt a realistic perspective, let’s give age its due and not sentimentalize its consequences.