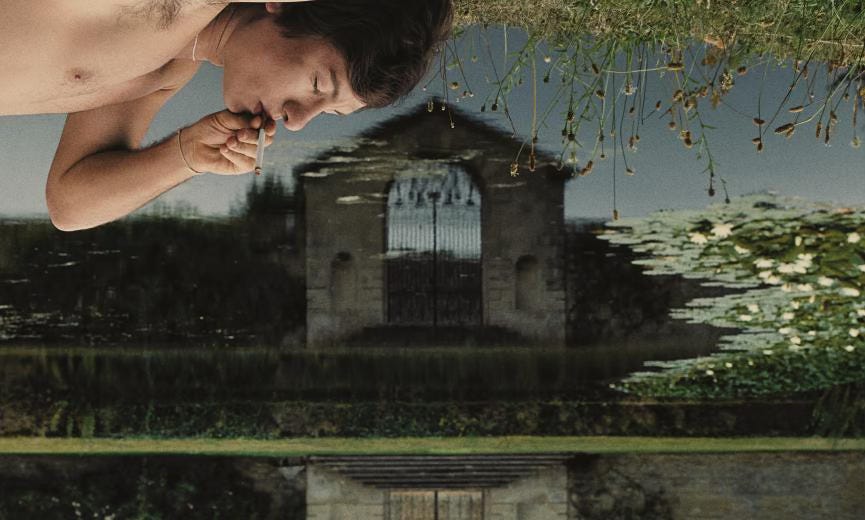

‘Saltburn’

Wealth, Privilege, Nudity, and Eating the Rich in Emerald Fennell’s “Saltburn” (2023)

Warning: The following article contains spoilers!

In a dizzy blur of decadence and deception, Emerald Fennell’s Saltburn serves as a sort of sick swan song for 2023, a year dubbed by the World Bank as “the year of inequality” due to stalling progress in combatting worldwide poverty and worsening wealth distribution in nations like the United Kingdom and the United States. With this current social and economic context in mind, the past decade’s eat-the-rich film genre trend makes sense as a sort of revenge-slash-success fantasy escapism in a world that feels hopeless and replete of opportunity. Saltburn sits nicely into this genre alongside other recent critical successes like The Menu (2022), Parasite (2019), Bodies Bodies Bodies (2022) The Purge (2013), and television series like The White Lotus (2021-present) and even recent seasons of Bravo’s various The Real Housewives franchises, in all of which we see the rich eaten or convinced to eat one another—figuratively speaking, of course.

In all likelihood, Saltburn will be remembered less for any supposed commentary on wealth inequality or decadence than it will be for its most controversial scenes: Oliver Quick (Barry Keoghan) sensuously tonguing Felix Catton’s (Jacob Elordi) dirty bathwater out of the drain—a moment already immortalized in consumable products—is one such example. Critics have been quick to call out the film’s failure to clearly articulate much criticism of grotesque wealth so much as it idolizes it, lusts after it, and consumes it through the eyes and experiences of its protagonist. While I would argue that the film’s portrayal of Oliver’s treacherous pursuit of the Catton family’s estate is itself a criticism of our wealth-deifying culture, it is also fair to point out that the film spends more time on aesthetics than it does on exposing society’s ills.

Aesthetics, however, are not in themselves meaningless or empty, so while the lavish interiors, unsettling sexuality, and sensational nudity in Saltburn may serve primarily to claw at the viewer’s attention, they also play a role in supporting the film’s themes. It is in the tension between ornament and nakedness, between wealth and poverty, and between the elite and the rest of us that the film seems to spend most of its time. Notably, nudity itself appears in aggressive and uncomfortable sexual moments in the film, apparently pointing to Oliver’s overarching motives to screw over and almost literally consume the Catton family, a metaphor perfectly exemplified by the aforementioned bathtub scene. But nudity also appears in more innocent, freeing scenes like a shared moment sunbathing nude in the middle of the estate’s wheat field, one of very few moments where we as viewers feel at ease within the story unfolding around us.

The film’s most iconic and memorable moment—the one that sparked conversations across the internet, dredged Sophie Ellis-Bextor’s 2001 disco-pop dance anthem back into the Billboard Top 100, and brought me to write this piece—comes right at the end of the film and spends the entire one-shot closing scene focused on Oliver, gloriously nude. By this point, through his long-con of the Catton family, Oliver has won the estate for himself to reign over as he pleases, and so he makes himself at home just like any of us might: by not just strolling from end to end nude, but prancing, gliding, spinning down its halls and through its rooms, a rapturous expression of conquest. It is in this moment when we finally see Oliver for who he is, out in the open, not hidden behind his motivations or his character, not shrouded in the disguises of class or wealth or role. We finally just see Oliver.

This final scene of Saltburn and its implications to the preceding sequence of events reminds the viewer of the film’s apparent similarities to another recent eat-the-rich fantasy, Rian Johnson’s cozy murder mystery, Knives Out (2019). Saltburn even employs rhyming scenes like showing Oliver gazing out from his castle balcony over the forlorn Catton family below, closely resembling Knives Out’s Marta (Ana de Armas) looking out over the recently displaced Thrombey family from the comfort of her newly inherited balcony, wrapped in a blanket, clutching a mug that reads “my house, my rules, my coffee.” While the two films are very similar in their setup and end result, their differences highlight just how disruptive Saltburn is to this genre of film and, ultimately, why many critics find its message hollow and uncomfortable.

Both films center on a young, less privileged protagonist taken in as something like a child by a ridiculously wealthy family with a storied legacy and an enormous, spectacular estate, to the delight of some members of the family and to the distrust of others. Over the course of each respective film, through death and revelation, the same interloping protagonist comes to inherit the estate out from under the family who had originally taken them in. The contrast between these stories rests in the motivations behind each protagonists’ involvement with the family, and the series of actions they took to wind up inheriting these estates. While Marta earned her seat on the throne through goodness and truth and a genuine connection with her late employer, Oliver won his by outsmarting and offing an entire bloodline, motivated seemingly by his obsession with wealth:

I don't think you're a spider, you're a moth. Quiet, harmless, drawn to shiny things, banging up against a window, and begging to get in.

-Alison Oliver as Veronica Catton, Saltburn (2023)

Oliver’s nude dance in Saltburn is his version of Marta’s “my house” mug in Knives Out, which I find to neatly contrast the brazenness and tenacity of Oliver’s character against Marta’s quiet, humble resoluteness. Marta is a likable, benevolent heir for whom you find yourself rooting throughout the film. Oliver is at least as unlikable as his benefactors, and while some may root for him or even delight in his dastardly deeds, he holds no claim to Marta’s moral high ground.

To further appreciate Saltburn’s naked finale, we ought to also take it in context and in contrast to the rest of the film, which from the sickly flicker of the title card’s font at the very introduction succeeds in stirring the viewer’s unease. There is something off here. This almost unwavering anxiety is maintained by placing the viewer in the perspective of Oliver, a supposedly low-income, half-orphaned student attending Oxford on a scholarship and who is severely and nauseatingly out of place among his carefully targeted new group of friends. He appears out of his element, surrounded by apex predators of class and privilege who, between pleasantries, are careful to remind him and one another of his place. His hosts may be awful to him at times, but they’re also quite generous, allowing him to stay at the Saltburn estate well beyond his welcome. Conversely, Oliver is grateful for their generosity, though he occasionally lets slip his mask, revealing his guile and untrustworthiness. After spending most of the film carrying some form of shame or guilt associated with his family, his social standing, and his lack of wealth—sometimes genuine and other times feigned for the sake of manipulating his hosts’ generosity—Oliver cajoles and consumes his way through the family until they all meet their end, until the estate is his, until he dances his way through its corridors denuded of any pretense he had donned prior.

Sex and nudity are not uncommon in this genre of film and television, even if blurred or obscured, but the role of nudity in Saltburn—especially the nudity in that final scene—is uncommon. For comparison, in Ruben Östlund’s Triangle of Sadness (2022), the loss of ornament and propriety and everything that separates the elite from the rest of us—as a result of the storm, sewage overflow, explosive vomiting, pirate invasion, and subsequent shipwreck—represents an abrupt stripping of wealth and status of the ship’s privileged guests. It acts as an actual and metaphorical nakedness and a sort of equalization before the hierarchy of the remaining cast of characters is flipped on its head and we find that the person most equipped to lead this band of survivors is not the Instagram model or the billionaire or even the ship’s captain, but the once-humble cleaning lady who had been tidying up after all of them just moments before the accident. Rather than using nakedness as a humbler, equalizer, or redistributor of power, Saltburn reserves nudity for its conqueror, its new king, its victor, who wears it proudly, like an ancient Olympian running a victory lap… after picking off his fellow athletes, sure.

If the message of the eat-the-rich genre is that the obscenely wealthy don’t deserve their riches but that perhaps some imaginary, hitherto destitute personality might be more deserving by dint of their uncorrupted nature, then the apparent message of Saltburn seems to be that, no, actually, maybe everyone is awful and undeserving and maybe the pursuit or acquisition of obscene wealth is just as inherently immoral and corrupt as being obscenely wealthy in the first place. And if it’s the past decade’s increasingly untenable distribution of wealth that spawned this recent spate of eat-the-rich films and television, then perhaps the prominent nudity of Saltburn is a similar response to our anxieties and distrust of one another as a result of deepening distrust in our institutions, nakedness eliciting the underlying, unknown truth we fear but rarely glimpse. Or perhaps it’s a response to an increasingly sex- and nudity-averse public, seeking to shock the viewer’s newly fragile sensibilities, to remind them of a time we were less easily alarmed by a penis or buttocks or sexuality. Or perhaps it’s all of this.

Ultimately, Saltburn is an aesthetically euphoric, morally muddy fever dream that the viewer can interpret with some liberty. Its lasting impact will certainly be that it got the Internet to celebrate and bicker over a male actor’s joyous and fully nude dance scene, the likes of which we don’t often see discussed in the public forum with such curiosity and gleeful obsession. That alone earns Saltburn its rightful place in the annals of pop culture.

Legit did a fist pump when I saw the title of this post, have been waiting to hear from others about it. I see it more about new power consuming old power (vs eat the rich) and the complexities of how that new power arises.

But! The sunbathing scene had me particularly curious, knowing the audience for this would be younger, of the impact it might have on opening up exploration for a different generation. There's definitely an unapologetic showcasing of the body in this and other movies, which mimics celebrities in real life (Kardashians in particular come to mind). Yet as that cycle of mimicry goes from art to life, I am genuinely curious about what might start to emerge as a rebellious spirit.

So many intriguing possibilities.

Yay for dancing naked thru the halls!