I have joked before that I named my blog “Almostwild” because I love the outdoors but dislike camping. That is partially true, but not entirely. There is a story behind the name, though, that leads somewhat sarcastically and somewhat sincerely to that one-line explanation, and it touches on some facets of the nudist and naturist community that often go unspoken but that, frankly, are ripe for discussion: What connection to nature does the modern naturist truly have? How natural is our sunscreened, flip-flopped, bespectacled nudity? Can modern humans ever truly be at one with nature in the ways we like to imagine it, or is that connection to the natural world something that we have irreparably lost along our path to civilization? Perhaps it is our pursuit of those ideals that makes us nudists and naturists, not necessarily their achievement, and in that pursuit we find meaning.

In the summer of 2018, not long before I started this blog, I made an exerted effort to finally visit some of the nudist clubs in the mountains of Western Oregon, near Portland where I was living at the time. One long weekend in particular, my husband and I travelled to Willamettans, a family nudist resort outside of Eugene, Oregon, nestled in the mountains but with all the amenities you’d expect from a semi-rustic mountain retreat: Pool, hot tub, sauna, hiking trails, a bar with cheap drinks and karaoke in the evenings, the works. My husband, who has a bad back and bad joints all around, loves the idea of camping but realistically cannot go backpacking or deep-woods camping, so bringing our tent, gear, and dog with us to a well-equipped campground was a perfect modification to make camping feasible for him. And… to be honest, no, I don’t love camping, but I do love and appreciate the outdoors, so this modified camping trip worked for me as well. I could spend time by the pool and grab a drink at the bar, but also cook hot dogs over a little grill and get an awful night’s sleep and make crappy instant coffee in the morning surrounded by woodlands and bugs and chirping birds… and I could be naked the whole time. The perfect camping compromise.

When we returned from our weekend of camping at Willamettans, I was excited to talk about how much fun it all was (despite the awful night’s sleep, etc., I did have a great time). I told a hardcore outdoorsy nudist friend of mine that we’d gone camping at a decked-out nudist resort, and told a somewhat granola coworker that we’d spent the weekend camping at a great spot with lots of fun amenities. I was excited! They were not! The response from both was, “that’s not real camping.” To be fair, sure. I know what “real” camping is. I spent much of my childhood going on camping trips with family, carrying gear in on a whitewater raft and spending a week camped along a river in the woods somewhere in Central Oregon with rattlesnakes and bugs and s’mores and using a log stretched over a pit in the ground as a toilet. I know what camping is. Is it really camping when you’ve pulled your Volvo up next to a grassy lot, pitched a tent 100 feet from a Porta-Potty, and can walk over to the pool to buy a hamburger from the pop-up lunch station? It’s up for debate. What’s clear is that there is an unspoken threshold of modern conveniences that separates “real” camping from “not” camping. Bringing your own tent you bought at REI? Real camping. Staying in a yurt, an RV, or a cabin? Not camping. Bringing flashlights and bug spray and a plastic cooler full of food you bought at the grocery store on your way in? Real camping. Bringing a portable charger so you can watch movies on your phone while you fall asleep in your flashlight-illuminated tent after eating the food from your plastic cooler and dousing yourself in bug spray? Not camping.

It’s interesting to me that many of the basic camping gear items that modern campers would consider necessary for “real” camping (such as a tent, flashlights, sleeping bags, fire starters, instant coffee, etc.), are luxuries compared to the tools available to, say, contestants on Naked and Afraid. The unspoken threshold allows for those conveniences, you see. It also strikes me as amusing that the premise of camping stems from recreational roots, an attempt to regain that lost connection to the natural world by experiencing it in a fun and controlled way. According to the National Wildlife Federation, camping as a pastime was invented in the 1800s to get people from the city out to experience wildlife, a novelty adventure for those who could afford it. In the UK, early accounts of British “pleasure boaters” tell of campers cooking with kettles, carrying in their own cookware and utensils and changes of clothes, and leaving broken Champagne bottles in their wake, so I think it’s safe to say that modern conveniences have been an integral part of camping for as long as “camping” has been around. Most interesting of all, however, is how even in our most pared-down existence, even when we escape to the woods or the desert or the lake to play primitive, most modern humans require a certain level of modern amenities and tools in order to survive… or at least to have an enjoyable time while surviving. And I think the lesson here is that that’s fine. If having those comforts allows campers to enjoy nature when they wouldn’t have otherwise, then it feels like a net positive.

This experience of debating what is and is not “real” camping with friends and coworkers was somewhat annoying, but mostly cordial. It stuck with me, though, and started to make me reconsider some of the ways I think about nudism and naturism as a whole, which in turn made this concept of being “almost wild” a perfect over-arching theme for a blog about nudism and naturism in the modern world. Modern humans simply are not the creatures we once were, even if our bodies and our skeletons look the same, even if we are physically capable of being those same creatures. We’ve moved on and, in the process, much of our connection to the natural world has been severed. Almost all of us live in cities or communities with quick access to all the amenities, services, and supplies we need not just to survive but to live long, easy, comfortable lives. No matter how much we love nature, love the outdoors, love the wilderness, that simply is no longer our natural habitat. For the naturist who values that connection to nature, the outdoors, and the elements, what, then, does it mean to reconnect with nature? For the nudist who values the human form and our natural state of nudity, what does it mean to seek freedom from the confines of clothing, to return to that natural state?

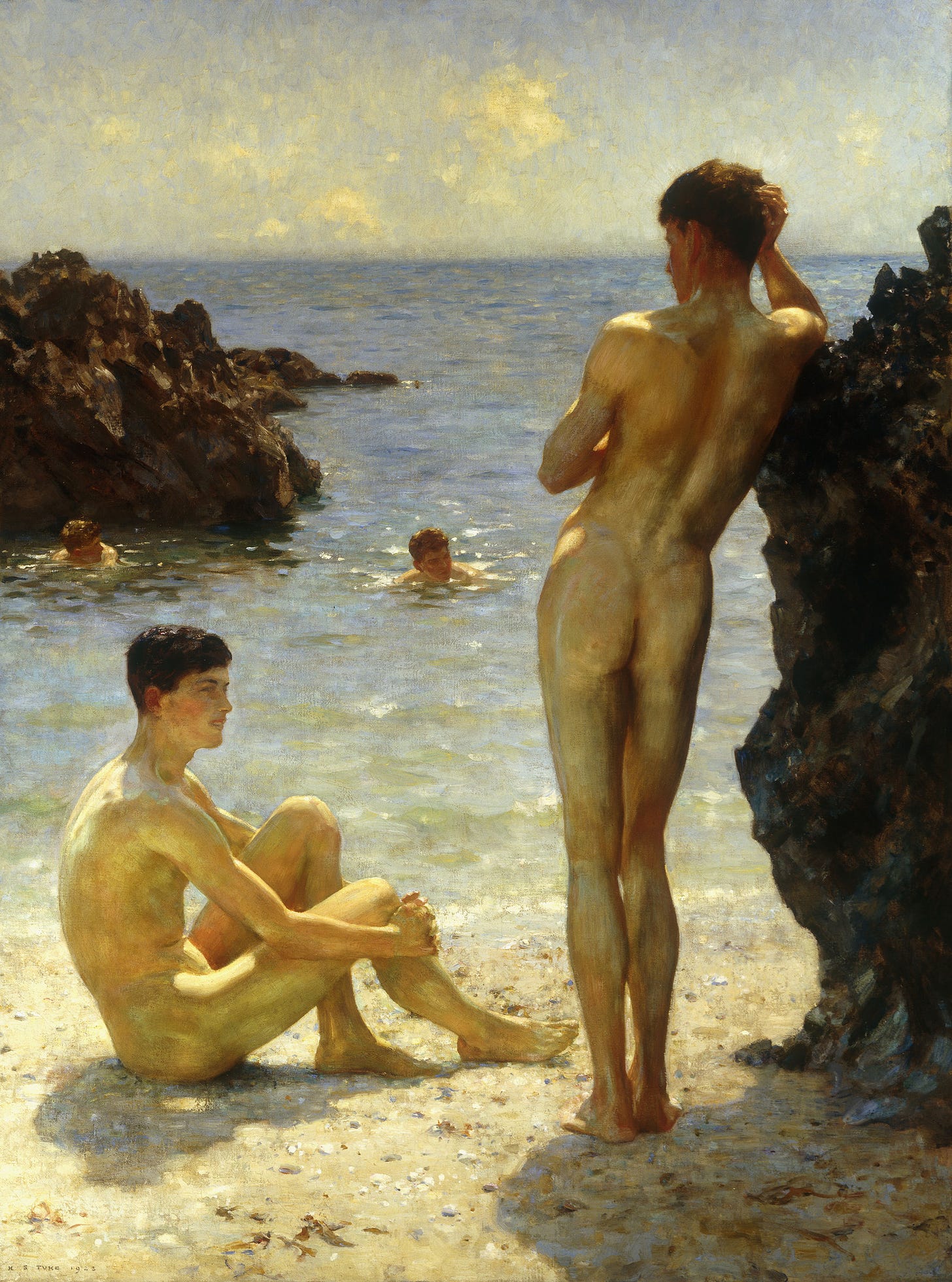

In this context, nudism and naturism are, like camping, novelty forms of modern recreation that imitate a simpler, more natural human existence. And I mean that in the most respectful and non-judgmental way possible, because there is nothing wrong with delighting in shedding these layers of modern life that can feel so heavy and burdensome. That’s the appeal! Just like in camping, we bring with us to nudism and naturism our modern conveniences, tool, ideologies, and philosophies. Where would we nudists be without our sunglasses, sunscreen, sandals, and sitting towels? Where would we free-hikers and naturists be without our backpacks, hiking shoes, wide-brimmed hats, and water bottles? None of these things exist in nature for us, yet they’re part of our enjoyment of nature and nudity. Try as we might to live a life free of textile goods, we can’t escape the fact that we still need things in order to not need things. And, likely, we still very much want things as well: Sunglasses that suit the shape of our face, sandals that express our personality, a towel in a color or pattern we like, a hat with a slogan or team logo that means something to us. Moreover, we bring with us our modern ideas and values, superimposing a philosophy of equality, community, and connection with nature and each other over top of a state of undress that, in our truly primitive, pre-textile days, meant absolutely nothing on its own. We make of nudism and naturism what we need it to be to feel a little more human, a little more natural… maybe a little more wild.

The point here is not that nudism and naturism are fake or artificial or meaningless, but that our practice of nudism and naturism is a sort of concerted effort to take back something we lost, to shed as many modern accessories and superficialities as we can in order to find meaning in our humanity, even if it’s all a sort of recreational imitation of wildness. What’s wrong with that? What’s so wrong about learning to love our bodies without all the clothes? What’s so wrong about trying to be a little closer to nature, even if it’s still mediated by some modern conveniences and tools? I think there’s something very special about the intention behind the practice of nudism and naturism, about the meaningful incorporation of simpler, more human, more honest, and more egalitarian values and behaviors into our everyday lives. That goes well beyond recreation and becomes something much deeper. When we discuss what it means to be a nudist or a naturist, we are often discussing those intentions that we bring with us and the learnings we gain, we are discussing those philosophies and the ways that we are able to engage with them. It matters less which precise rules or steps we follow to get there, as long as we are all respectful. Just like camping, we each come to the nudist and naturist community with a different comfort level, with a different degree of engagement, and with a different threshold for what feels right: Some nudists will spend nearly every moment of their day nude while others may only be interested in the occasional trip to a nude beach or club. There’s no need to qualify or stratify those experiences, rather, we can celebrate that we are all here from different places, for different reasons, and there is room for everyone.

This is what inspired the name and theme of my blog. “Almostwild” is a play on this age-old relationship between the natural world that we have lost and our efforts to return to it on our own terms, with our own values and intentions and modern conveniences. Our enjoyment of nudism and naturism may well be a recreational imitation of wildness, but that mediated wildness carries a great deal of purpose, a philosophy for living, an opportunity for growth, and an exploration of what it means to be human. Recognizing that there’s no one right way to pursue that wildness, or that connection to wildness, is a good place to start, and it opens the conversation to all kinds of other intersecting topics, ideas, and communities pursuing the same sorts of connection, equality, and meaning. Thank you for joining me while I write about those pursuits and intersections.

Car camping and wilderness camping are both “real” activities that take us out of the day to day grind and allow us to explore other aspects of ourselves. We cannot unlearn modernity in either setting.

We can be naked in fenced out door and freehiking “wilderness” camping environments too - weather and bugs permitting. That is so much the better!

That's not REAL (fill-in-the-blank) is just "gatekeeping." Everyone should just do their own thing in their own time as long as they aren't infringing on others.